Wikiprojekt:Tłumaczenie artykułów/Pluton

|

|

Ten artykuł jest obecnie tłumaczony z języka angielskiego. Podstawę stanowi Pluto. Zobacz obecny kształt artykułu. |

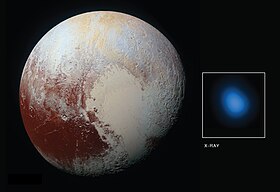

Computer-generated map of Pluto from Hubble images, synthesised true colour[a] and among the highest resolutions possible with current technology | |

| Odkrywca | |

|---|---|

| Data odkrycia |

18 luty 1930 |

| Numer kolejny |

134340 |

| Charakterystyka fizyczna | |

| Masa | |

| Albedo | |

| Średnia temperatura powierzchni |

yes K |

Pluton - (oznaczenie oficjalne: (134340) Pluton) planeta karłowata, plutoid, najjaśniejszy obiekt pasa Kuipera, należy do szerszej grupy obiektów transneptunowych. Był pierwszym odkrytym obiektem w Pasie Kuipera.

Został odkryty w 1930 roku przez amerykańskiego astronoma Clyde’a Tombaugha i od czasu odkrycia do 2006 roku Pluton oficjalnie był uznawany za dziewiątą planetę Układu Słonecznego. Po 1992 roku w związku z odkryciem kilku obiektów podobnej wielkości w Pasie Kupiera definicja planety została kwestionowana. W 2005 r. została odkryta kolejna planeta karłowata (136199) Eris, w dysku rozproszonym, która jest 27% masywniejsza niż Pluton. 24 sierpnia 2006 roku decyzją Międzynarodowej Unii Astronomicznej, zmieniono definicję planety, w wyniku czego Pluton został zaliczony do nowoutworzonej klasy obiektów – planet karłowatych[12] Pluton jest największą i drugą najbardziej masywną znaną planetą karłowatą w Układzie Słonecznym oraz dziewiątym co do wielkości i dziesiątym najbardziej masywnym znanym obiektem bezpośrednio orbitującym Słońce. Pod względem objętości jest to największy znany obiekt trans-neptunowy, ale jest mniej masywny niż Eris. Podobnie jak inne obiekty w pasie Kuipera, Pluton składa się przede wszystkim z lodu i skał i jest stosunkowo mały - ma około jednej szóstej masy Księżyca i jedną trzecią jego objętości. Ma umiarkowanie mimośrodową i nachyloną orbitę, podczas której jego odległość od Słońca waha się od 30 do 49 jednostek astronomicznych (4,4-7,4 miliarda km). Oznacza to, że Pluton okresowo jest bliżej Słońca niż Neptun, stabilny rezonans orbitalny zapobiega kolizji z Neptunem. Światło słoneczne potrzebuje około 5,5 godziny, aby dotrzeć do Plutona znajdującego się w średniej odległości (39.5 AU).

Pluton ma pięć znanych księżyców: Charon (największy, o średnicy niewiele większej od Plutona), Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra. Pluton i Charon są czasami uważane za system podwójny, ponieważ barycentrum ich orbit nie leży w żadnym ciele.

14 lipca 2015 r. sonda New Horizons była pierwszym statkiem kosmicznym, który przeleciał obok Plutona. Podczas krótkiego przelotu New Horizons dokonała pomiarów i obserwacji Plutona i jego księżyców. We wrześniu 2016 r. Astronomowie ogłosili, że czerwonawo-brązowa czapa północnego bieguna Charona składa się z tholin, makrocząsteczek organicznych, które mogą być składnikami do pojawienia się życia i produkowanych z metanu, azotu i innych gazów uwalnianych z atmosfery Plutona i przekazywanych na orbitujący w odległosci około 19 000 km księżyc.

Historia[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Odkrycie[edytuj | edytuj kod]

W latach czterdziestych XIX wieku Urbain Le Verrier użył mechaniki newtonowskiej do przewidywania położenia nieodkrytej planety Neptuna po analizie perturbacji orbity Urana[13]. Późniejsze obserwacje Neptuna pod koniec XIX wieku skłoniły astronomów do spekulacji, że orbita Urana została zakłócona przez inną planetę oprócz Neptuna. W 1906 r. Percival Lowell - bogaty bostończyk, który założył Lowell Observatory we Flagstaff w Arizonie w 1894 r. - rozpoczął szeroko zakrojony projekt w poszukiwaniu możliwej dziewiątej planety, którą nazwał "planetą X".[14]. Do 1909 roku Lowell i William H. Pickering zasugerowali kilka możliwych współrzędnych niebieskich dla takiej planety[15]. Lowell i jego obserwatorium przeprowadzali poszukiwania aż do jego śmierci w 1916 roku, ale bezskutecznie. Lowell i jego badacze zdobyli dwa niewyraźne obrazy Plutona w dniu 19 marca i 7 kwietnia 1915 roku, ale nie zostały one uznane za obrazy planety[15][16]. Istnieje czternaście innych znanych wstępnych obserwacji, a najstarsze z nich pochodzi z Obserwatorium Yerkesa z 20 sierpnia 1909 r[17].

Wdowa po Percivalu, Constance Lowell, rozpoczęła dziesięcioletnią batalię prawniczą z Obserwatorium Lowella o spuściznę jej męża, a poszukiwanie Planety X rozpoczęło się dopiero w 1929 r..[18] Vesto Melvin Slipher, dyrektor obserwatorium, dał zadanie zlokalizowania Planet X dwudziestotrzyletniemu Clyde Tombaugh, który właśnie przybył do obserwatorium po tym, jak Slipher był pod wrażeniem próbki jego astronomicznego rysunku[18].

Zadaniem Tombaugh było systematyczne obrazowanie nocnego nieba w parach fotografii, a następnie sprawdzenie każdej pary i ustalenie, czy jakiekolwiek obiekty zmieniły swoją pozycję. Używając komparatora i porównując mrugnięcia, szybko przesunął się w przód i w tył pomiędzy widokami każdej z płytek, aby stworzyć iluzję ruchu dowolnych obiektów, które zmieniły położenie lub wygląd na fotografiach. 8 lutego 1930 roku, po prawie roku poszukiwań, Tombaugh odkrył możliwy obiekt poruszający się na płytach fotograficznych wykonanych w dniach 23 i 29 stycznia. Mniejsza jakość zdjęcia wykonanego 21 stycznia pomogła potwierdzić ruch[19]. Po tym, jak obserwatorium uzyskało kolejne zdjęcia potwierdzające, wiadomość o odkryciu została przekazana Harvard College Observatory 13 marca 1930 r.[15]

Nazwa[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Odkrycie trafiło na pierwsze strony gazet na całym świecie[20]. Obserwatorium Lowella, mające prawo wyboru nazwy nowego obiektu, otrzymało ponad 1000 propozycji z całego świata, od Atlasa po Zymala[21]. Tombaugh nalegał, by Slipher zasugerował nazwę nowego obiektu szybko, zanim zrobi to ktoś inny[21]. Constance Lowell zaproponowała "Zeus", następnie "Percival" i wreszcie "Constance". Propozycje te zostały zignorowane[22].

Nazwa Pluton została zaproponowana przez jedenastoletnią uczennicę z Oxfordu Venetię Burney interesującą się mitologią klasyczną[23]. Zasugerowała to podczas rozmowy z jej dziadkiem Falconer Madan, byłym bibliotekarzem w Bibliotece Bodlejańskiej Uniwersytetu Oksfordzkiego, który przekazał tę nazwę profesorowi astronomii Hubertowi Turnerowi, który przekazał ją kolegom w Stanach Zjednoczonych[23].

Każdy członek Obserwatorium Lowella mógł głosować na krótkiej liście trzech potencjalnych nazw: Minerva (która już była nazwą asteroidy), Cronus (który utracił reputację dzięki propozycjom niepopularnego astronoma Thomasa Jeffersona Jacksona), i Plutona. Pluto otrzymał każdy głos[24]. Nazwa została oficjalnie ogłoszona 1 maja 1930 roku[23][25]. Po ogłoszeniu Madan dał Venetii 5 funtów (ok. 316 GBP w 2021[i]) jako nagrodę[23].

Ostatecznemu wyborowi imienia częściowo pomógł fakt, że dwie pierwsze litery „Plutona” są inicjałami Percivala Lowella. Następnie stworzono symbol astronomiczny Plutona ![]() .[26].

Astrologiczny symbol Plutona przypomina Neptuna (

.[26].

Astrologiczny symbol Plutona przypomina Neptuna (![]() ), ale w miejscu trójzębu ma bolec (

), ale w miejscu trójzębu ma bolec (![]() ).

).

wkrótce nazwa przyjęła się w szerszej kulturrze. W 1930 r. Walt Disney przedstawił Myszce Miki psiego towarzysza o imieniu Ppsa Pluto, chociaż animator Walt Disney Company Ben Sharpsteen nie mógł potwierdzić, dlaczego podano nazwę[27]. W 1941 Glenn T. Seaborg nazwał nowo utworzony pierwiastek pluton , zgodnie z tradycją nazywania pierwiastków nazwami nowo odkrytych planet, po uranium , który został nazwany na cześć Urana i neptunium, który został nazwany na cześć Neptuna[28].

Most languages use the name "Pluto" in various transliterations.[j] In Japanese, Houei Nojiri suggested the translation Szablon:Nihongo3, and this was borrowed into Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese (which instead uses "Sao Diêm Vương", which was derived from the Chinese term 閻王 (Yánwáng), as "minh" is a homophone for the Sino-Vietnamese words for "dark" (冥) and "bright" (明))[29][30][31]. Some Indian languages use the name Pluto, but others, such as Hindi, use the name of Yama, the God of Death in Hindu and Buddhist mythology[30]. Polynesian languages also tend to use the indigenous god of the underworld, as in Māori Whiro[30].

Obalenie teorii planety X[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Po znalezieniu Plutona jego słabość i brak usuwalnego dysku podważają teorię Lovella, że był on Planetą X krążącą za orbitą Neptuna[14]. w xx dokonano rewizji szacunkowej masy Plutona[32].

| rok | masa | Szacujący |

|---|---|---|

| 1915 | 7 mas Ziemi | Lowell (prediction for Planet X)[14] |

| 1931 | 1 masa Ziemi | Nicholson & Mayall[33][34][35] |

| 1948 | 0.1 (1/10) masy Ziemi | Kuiper[36] |

| 1976 | 0.01 (1/100) masy Ziemi | Cruikshank, Pilcher, & Morrison[37] |

| 1978 | 0.0015 (1/650) masy Ziemi | Christy & Harrington[38] |

| 2006 | 0.00218 (1/459) masy Ziemi | Buie et al.[39] |

Astronomowie początkowo obliczali masę planety na podstawie przypuszczalnego wpływu na Neptuna i Urana. W 1931 r. masę planety obliczono jako mniej więcej masę Ziemi, a dalsze obliczenia z 1948 r. sprowadzają masę do mniej więcej masy Marsa[34][36]. W 1976 r. Dale Cruikshank, Carl Pilcher i David Morrison z University of Hawaii po raz pierwszy obliczyli masę Plutona, stwierdzając, że pasuje ona do lodu metanowego; oznaczało to, że Pluton musiał być wyjątkowo jasny ze względu na swoje rozmiary, a zatem nie mógł być większy niż 1% masy Ziemi.[37] (Pluto's albedo is 1.4–1.9 times that of Earth[3].)

W 1978 roku odkrycie księżyca Plutona Charona po raz pierwszy pozwoliło zmierzyć masę Plutona: wynosiła ona około 0,2% masy Ziemi i była zdecydowanie zbyt mała, aby tłumaczyć rozbieżności w orbicie Urana. Kolejne poszukiwania alternatywnej Planety X, w szczególności przez Roberta Suttona Harringtona[40], zakończyły się niepowodzeniem. W 1992 r. Myles Standish wykorzystał dane z sondy [[[Voyager 2]] przelatującej koło Neptuna w 1989 r. zrewidował szacunki masy Neptuna o 0,5% - ilość porównywalną z masą Marsa - aby ponownie obliczyć jego działanie grawitacyjne na Urana. Po dodaniu nowych liczb zniknęły rozbieżności, a wraz z nimi potrzeba odkrycia Planety X[41]. Dzisiaj większość naukowców zgadza się, że Planeta X, którą zdefinował Lowell, nie istnieje[42]. W 1915 Lowell dokonał prognozy orbity i pozycji planety X, która była dość zbliżona do faktycznej orbity Plutona i jej pozycji w tym czasie; Ernest W. Brown stwierdził wkrótce po odkryciu Plutona, że był to zbieg okoliczności[43], a view still held today[41].

klasyfikacja[edytuj | edytuj kod]

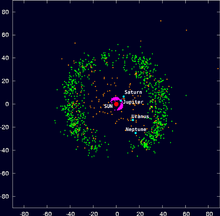

Szablon:Further Szablon:TNO imagemap

Od 1992 roku odkryto wiele ciał na orbicie w tej samej objętości co Pluton, co dowodzi, że Pluton należy do populacji obiektów Pasa Kuipera. To sprawiło, że jego oficjalny status jako kontrowersyjnej planety wzbudził wiele pytań, czy Pluton powinien być rozpatrywany razem z otaczającymi go obiektami, czy też osobno. Dyrektorzy muzeum i planetarium sporadycznie tworzyli kontrowersje, pomijając Plutona w planetarnych modelach Układu Słonecznego. Planetarium Haydena zostało ponownie otwarte - w lutym 2000 r., Po renowacji - z modelem tylko ośmiu planet, które trafiły na pierwsze strony gazet prawie rok później[44].

Ponieważ w regionie odkryto obiekty coraz bardziej zbliżone do Plutona, argumentowano, że Plutona należy przeklasyfikować jako jeden z obiektów pasa Kuipera, podobnie jak Ceres, Pallas, Juno i Vesta stracili status planety po odkryciu wielu innych planetoid . 29 lipca 2005 r. Astronomowie z Caltech ogłosili odkrycie nowego trans-neptunowego obiektu Eris, który był znacznie masywniejszy od Plutona i najbardziej masywnego obiektu odkrytego w Układzie Słonecznym od czasów Trytona w 1846 r. Jego odkrywcy i prasa początkowo nazwał ją dziesiątą planetą, chociaż w tamtym czasie nie było oficjalnego konsensusu, czy nazwać ją planetą[45]. Inni członkowie społeczności astronomicznej uważali to odkrycie za najsilniejszy argument przemawiający za przeklasyfikowaniem Plutona na planetę karłowatą[46].

klasyfikacja IAU[edytuj | edytuj kod]

W sierpniu 2006 r odbyła się debata. Rezolucja Międzynarodowej Unii Astronomicznej (IAU), stworzyła oficjalną definicję terminu „planeta”. Zgodnie z rezolucją istnieją trzy warunki, aby obiekt w Układzie Słonecznym był uważany za planetę:

- Obiekt musi znajdować się na orbicie wokół Słońca.

- Obiekt musi być wystarczająco masywny, aby mógł zostać zaokrąglony przez własną grawitację.Jego grawitacja powinna przyciągnąć go do kształtu określonego przez równowagę hydrostatyczną.

- Musi mieć oczyścić swoją orbitę [47][48].

Pluto fails to meet the third condition. Its mass is substantially less than the combined mass of the other objects in its orbit: 0.07 times, in contrast to Earth, which is 1.7 million times the remaining mass in its orbit[46][48]. The IAU further decided that bodies that, like Pluto, meet criteria 1 and 2, but do not meet criterion 3 would be called dwarf planets. In September 2006, the IAU included Pluto, and Eris and its moon Dysnomia, in their Minor Planet Catalogue, giving them the official minor planet designations "(134340) Pluto", "(136199) Eris", and "(136199) Eris I Dysnomia"[49]. Had Pluto been included upon its discovery in 1930, it would have likely been designated 1164, following 1163 Saga, which was discovered a month earlier[50].

There has been some resistance within the astronomical community toward the reclassification[51][52][53]. Alan Stern, principal investigator with NASA's New Horizons mission to Pluto, derided the IAU resolution, stating that "the definition stinks, for technical reasons"[54]. Stern contended that, by the terms of the new definition, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Neptune, all of which share their orbits with asteroids, would be excluded[55]. He argued that all big spherical moons, including the Moon, should likewise be considered planets[56]. He also stated that because less than five percent of astronomers voted for it, the decision was not representative of the entire astronomical community[55]. Marc W. Buie, then at the Lowell Observatory petitioned against the definition[57]. Others have supported the IAU. Mike Brown, the astronomer who discovered Eris, said "through this whole crazy circus-like procedure, somehow the right answer was stumbled on. It's been a long time coming. Science is self-correcting eventually, even when strong emotions are involved."[58]

Public reception to the IAU decision was mixed. Many accepted the reclassification, but some sought to overturn the decision with online petitions urging the IAU to consider reinstatement. A resolution introduced by some members of the California State Assembly facetiously called the IAU decision a "scientific heresy"[59]. The New Mexico House of Representatives passed a resolution in honor of Tombaugh, a longtime resident of that state, that declared that Pluto will always be considered a planet while in New Mexican skies and that March 13, 2007, was Pluto Planet Day[60][61]. The Illinois Senate passed a similar resolution in 2009, on the basis that Clyde Tombaugh, the discoverer of Pluto, was born in Illinois. The resolution asserted that Pluto was "unfairly downgraded to a 'dwarf' planet" by the IAU."[62] Some members of the public have also rejected the change, citing the disagreement within the scientific community on the issue, or for sentimental reasons, maintaining that they have always known Pluto as a planet and will continue to do so regardless of the IAU decision[63].

In 2006, in its 17th annual words-of-the-year vote, the American Dialect Society voted plutoed as the word of the year. To "pluto" is to "demote or devalue someone or something"[64].

Researchers on both sides of the debate gathered in August 2008, at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory for a conference that included back-to-back talks on the current IAU definition of a planet[65]. Entitled "The Great Planet Debate"[66], the conference published a post-conference press release indicating that scientists could not come to a consensus about the definition of planet[67]. In June 2008, the IAU had announced in a press release that the term "plutoid" would henceforth be used to refer to Pluto and other objects that have an orbital semi-major axis greater than that of Neptune and enough mass to be of near-spherical shape[68][69][70].

Orbita[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Pluto was discovered in 1930 near the star δ Geminorum, and merely coincidentally crossing the ecliptic at this time of discovery. Pluto moves about 7 degrees east per decade with small apparent retrograde motion as seen from Earth. Pluto was closer to the Sun than Neptune between 1979 and 1999. |

Okres obiegu Plutona wokół Słońca wynosi obecnie około 248 lat. Jego charakterystyka orbitalna jest zasadniczo różna od charakterystyki planet, które podążają za niemal okrągłymi orbitami wokół Słońca w pobliżu płaskiej płaszczyzny odniesienia zwanej ekliptyką. Natomiast orbita Plutona jest umiarkowanie nachylona względem ekliptyki (ponad 17 °) i umiarkowanie ekscentrycznej (eliptycznej). Ta ekscentryczność oznacza, że niewielki obszar orbity Plutona znajduje się bliżej Słońca niż Neptun. Barycentrum układu Pluton-Charon weszło w peryhelium 5 września 1989 roku[4],[k] I od 7 lutego 1979 r do 11 lutego 1999 r. znajdował się bliżej Słońca niż Neptun[71].

W dłuższej perspektywie orbita Plutona jest chaotyczna. Za pomocą symulacji komputerowych można przewidzieć jego pozycję na kilka milionów lat (zarówno w przód, jak i wstecz), ale w okresie dłuższym niż czas Lapunowa wynoszący od 10 do 20 milionów lat, obliczenia stają się spekulacyjne: Pluton jest wrażliwy na niezmiernie małe szczegóły Układu Słonecznego, trudne do przewidzenia czynniki, które stopniowo zmienią pozycję Plutona na jego orbicie[72][73].

The semi-major axis of Pluto's orbit varies between about 39.3 and 39.6 au with a period of about 19,951 years, corresponding to an orbital period varying between 246 and 249 years. The semi-major axis and period are presently getting longer[74].

Związek z Neptunem[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Mimo, że orbita Plutona wydaje się przekraczać orbitę Neptuna widzianą bezpośrednio z góry, orbity tych dwóch obiektów są ustawione tak, że nigdy nie zderzają się, a nawet nie zbliżają.

Istnieje kilka powodów, dlaczego.

Na najprostszym poziomie, można zbadać że dwie widoczne orbity się nie przecinają. Kiedy Pluton jest najbliżej Słońca, a więc najbliżej orbity Neptuna, patrząc z góry, jest to również najdalej powyżej ścieżki Neptuna. Orbita Plutona przechodzi około 8 j.a powyżej Neptuna, co zapobiegania kolizji

Obie orbity się nie przecinają. Gdy Pluton jest najbliżej Słońca, a stąd najbliżej orbity Neptuna, widzianej z góry, jest również najdalej wysuniętą ścieżką Neptuna. Orbita Plutona przechodzi około 8 AU powyżej orbity Neptuna, zapobiegając kolizji[75][76][77].

This alone is not enough to protect Pluto; perturbations from the planets (especially Neptune) could alter Pluto's orbit (such as its orbital precession) over millions of years so that a collision could be possible. However, Pluto is also protected by its 2:3 orbital resonance with Neptune: for every two orbits that Pluto makes around the Sun, Neptune makes three. Each cycle lasts about 495 years. This pattern is such that, in each 495-year cycle, the first time Pluto is near perihelion, Neptune is over 50° behind Pluto. By Pluto's second perihelion, Neptune will have completed a further one and a half of its own orbits, and so will be nearly 130° ahead of Pluto. Pluto and Neptune's minimum separation is over 17 AU, which is greater than Pluto's minimum separation from Uranus (11 AU)[77]. The minimum separation between Pluto and Neptune actually occurs near the time of Pluto's aphelion[74].

The 2:3 resonance between the two bodies is highly stable, and has been preserved over millions of years[78]. This prevents their orbits from changing relative to one another, and so the two bodies can never pass near each other. Even if Pluto's orbit were not inclined, the two bodies could never collide[77]. The long term stability of the mean-motion resonance is due to phase protection. If Pluto's period is slightly shorter than 3/2 of Neptune its orbit relative to Neptune will drift, causing it to make closer approaches behind Neptune's orbit. The strong gravitational pull between the two causes angular momentum to be transferred to Pluto, at Neptune's expense. This moves Pluto into a slightly larger orbit, where it travels slightly more slowly, according to Kepler's third law. After many such repetitions, Pluto is sufficiently slowed, and Neptune sufficiently sped up, that Pluto orbit relative to Neptune drifts in the opposite direction until the process is reversed. The whole process takes about 20,000 years to complete[77][78][79].

Other factors[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Numerical studies have shown that over millions of years, the general nature of the alignment between the orbits of Pluto and Neptune does not change[75][74]. There are several other resonances and interactions that enhance Pluto's stability. These arise principally from two additional mechanisms (besides the 2:3 mean-motion resonance).

First, Pluto's argument of perihelion, the angle between the point where it crosses the ecliptic and the point where it is closest to the Sun, librates around 90°.[74] This means that when Pluto is closest to the Sun, it is at its farthest above the plane of the Solar System, preventing encounters with Neptune. This is a consequence of the Kozai mechanism[75], which relates the eccentricity of an orbit to its inclination to a larger perturbing body—in this case Neptune. Relative to Neptune, the amplitude of libration is 38°, and so the angular separation of Pluto's perihelion to the orbit of Neptune is always greater than 52° (90°–38°). The closest such angular separation occurs every 10,000 years[78].

Second, the longitudes of ascending nodes of the two bodies—the points where they cross the ecliptic—are in near-resonance with the above libration. When the two longitudes are the same—that is, when one could draw a straight line through both nodes and the Sun—Pluto's perihelion lies exactly at 90°, and hence it comes closest to the Sun when it is highest above Neptune's orbit. This is known as the 1:1 superresonance. All the Jovian planets, particularly Jupiter, play a role in the creation of the superresonance[75].

Quasi-satellite[edytuj | edytuj kod]

In 2012, it was hypothesized that 15810 Arawn could be a quasi-satellite of Pluto, a specific type of co-orbital configuration[80]. According to the hypothesis, the object would be a quasi-satellite of Pluto for about 350,000 years out of every two-million-year period[80][81]. This hypothesis was disproven in 2016, when more-accurate observations of the position of Arawn were made by New Horizons[82].

Obieg[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Jeden okres obrotu Plutona wokół własnej osi wynosi 6.39 dnia ziemskiego[83]. Podobnie jak Uran, Pluton obraca się po swojej "stronie" w swojej płaszczyźnie orbitalnej, z osiowym przechyleniem o 120 °, a więc jej sezonowa zmienność jest ekstremalna; podczas przesilenia jedna czwarta jego powierzchni jest w ciągłym świetle dziennym, podczas gdy inna czwarta jest w ciągłym mroku[84]. The reason for this unusual orientation has been debated. Research from University of Arizona has suggested that it may be due to the way that a body's spin will always adjust to minimise energy. This could mean a body reorienting itself to put extraneous mass near the equator and regions lacking mass tend towards the poles. This is called polar wander[85]. According to a paper released from the University of Arizona, this could be caused by masses of frozen nitrogen building up in shadowed areas of the dwarf planet. These masses would cause the body to reorient itself, leading to its unusual axial tilt of 120°. The buildup of nitrogen is due to Pluto's vast distance from the Sun. At the equator, temperatures can drop to −240 °C (−400,0 °F; 33,1 K), causing nitrogen to freeze as water would freeze on Earth. The same effect seen on Pluto would be observed on Earth if the Antarctic ice sheet was several times larger[86].

Geologia[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Powierzchnia[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Równiny na powierzchni Plutona składają się w ponad 98% z lodu azotowego, ze śladami metanu i tlenku węgla[87]. Azot i tlenek węgla są najliczniej występujące na powierzchni Plutona przeciwko Charonowi (około 180 ° długości geograficznej, gdzie znajduje się zachodni płat Tombaugh Regio, Sputnik Planitia), podczas gdy metan występuje najliczniej w pobliżu 300 ° E.[88] Góry składają się z lodu wodnego[89]. Pluto's surface is quite varied, with large differences in both brightness and color[90]. Pluto is one of the most contrastive bodies in the Solar System, with as much contrast as Saturn's moon Iapetus[91]. The color varies from charcoal black, to dark orange and white[92]. Pluto's color is more similar to that of Io with slightly more orange and significantly less red than Mars[93]. Notable geographical features include Tombaugh Regio, or the "Heart" (a large bright area on the side opposite Charon), Cthulhu Macula[94], or the "Whale" (a large dark area on the trailing hemisphere), and the "Brass Knuckles" (a series of equatorial dark areas on the leading hemisphere). Sputnik Planitia, the western lobe of the "Heart", is a 1,000 km-wide basin of frozen nitrogen and carbon monoxide ices, divided into polygonal cells, which are interpreted as convection cells that carry floating blocks of water ice crust and sublimation pits towards their margins[95][96][97]; there are obvious signs of glacial flows both into and out of the basin[98][99]. It has no craters that were visible to New Horizons, indicating that its surface is less than 10 million years old.[100] Latest studies have shown that the surface has an age of Szablon:Val years[101]. The New Horizons science team summarized initial findings as "Pluto displays a surprisingly wide variety of geological landforms, including those resulting from glaciological and surface–atmosphere interactions as well as impact, tectonic, possible cryovolcanic, and mass-wasting processes."[102] Szablon:Multiple image

Struktura wewnętrzna[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Pluto's density is Szablon:Val[102]. Because the decay of radioactive elements would eventually heat the ices enough for the rock to separate from them, scientists expect that Pluto's internal structure is differentiated, with the rocky material having settled into a dense core surrounded by a mantle of water ice. The diameter of the core is hypothesized to be approximately Szablon:Val, 70% of Pluto's diameter[103]. It is possible that such heating continues today, creating a subsurface ocean of liquid water 100 to 180 km thick at the core–mantle boundary[103][104][105]. In September 2016, scientists at Brown University simulated the impact thought to have formed Sputnik Planitia, and showed that it might have been the result of liquid water upwelling from below after the collision, implying the existence of a subsurface ocean at least 100 km deep.[106] Pluto has no magnetic field[107].

Masa i rozmiar[edytuj | edytuj kod]

| Year | Radius | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 1195 km | Millis, et al.[108] (if no haze)[109] |

| 1993 | 1180 km | Millis, et al. (surface & haze)[109] |

| 1994 | 1164 km | Young & Binzel[110] |

| 2006 | 1153 km | Buie, et al.[39] |

| 2007 | 1161 km | Young, Young, & Buie[111] |

| 2011 | 1180 km | Zalucha, et al.[112] |

| 2014 | 1184 km | Lellouch, et al.[113] |

| 2015 | 1187 km | New Horizons measurement (from optical data)[114] |

| 2017 | 1188.3 km | New Horizons measurement (from radio occultation data)[115][94] |

Pluto's diameter is Szablon:Val[115] and its mass is Szablon:Val, 17.7% that of the Moon (0.22% that of Earth)[116]. Its surface area is Szablon:Val, or roughly the same surface area as Russia. Its surface gravity is 0.063 g (compared to 1 g for Earth).

Odkrycie satelity Plutona Charona w 1978 r. umożliwiło określenie masy układu Pluton – Charon przez zastosowanie sformułowanie trzeciego Keplera prawo. Obserwacje układu Pluton Charon pozwoliły naukowcom na dokładniejsze ustalenie średnicy Plutona, podczas gdy odkrycie optyki adaptywnej pozwoliło im dokładniej określić jego kształt[117].

With less than 0.2 lunar masses, Pluto is much less massive than the terrestrial planets, and also less massive than seven moons: Ganymede, Titan, Callisto, Io, the Moon, Europa, and Triton. The mass is much less than thought before Charon was discovered.

Pluto is more than twice the diameter and a dozen times the mass of the dwarf planet Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt. It is less massive than the dwarf planet Eris, a trans-Neptunian object discovered in 2005, though Pluto has a larger diameter of 2376.6 km[115] compared to Eris's approximate diameter of 2326 km.[118]

Określenie wielkości Plutona było skomplikowane z powdodu jego atmosfery[111], zamglenia węglowodorów[109]. In March 2014, Lellouch, de Bergh et al. published findings regarding methane mixing ratios in Pluto's atmosphere consistent with a Plutonian diameter greater than 2360 km, with a "best guess" of 2368 km.[113] On July 13, 2015, images from NASA's New Horizons mission Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), along with data from the other instruments, determined Pluto's diameter to be 2 370 km (1 470 mi)[118][119], which was later revised to be 2 372 km (1 474 mi) on July 24[114], and later to Szablon:Val[102]. Using radio occultation data from the New Horizons Radio Science Experiment (REX), the diameter was found to be Szablon:Val[115].

Atmosfera[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Pluton posiada rzadką atmosferę składającą się z azotu (N2), metanu (CH4), i tlenku węgla (CO), which are in equilibrium with their ices on Pluto's surface[120][121]. According to the measurements by New Horizons, the surface pressure is about 1 Pa (10 μbar)[102], roughly one million to 100,000 times less than Earth's atmospheric pressure. It was initially thought that, as Pluto moves away from the Sun, its atmosphere should gradually freeze onto the surface; studies of New Horizons data and ground-based occultations show that Pluto's atmospheric density increases, and that it likely remains gaseous throughout Pluto's orbit[122][123]. New Horizons observations showed that atmospheric escape of nitrogen to be 10,000 times less than expected[123]. Alan Stern has contended that even a small increase in Pluto's surface temperature can lead to exponential increases in Pluto's atmospheric density; from 18 hPa to as much as 280 hPa (three times that of Mars to a quarter that of the Earth). At such densities, nitrogen could flow across the surface as liquid[123]. Just like sweat cools the body as it evaporates from the skin, the sublimation of Pluto's atmosphere cools its surface[124]. The presence of atmospheric gases was traced up to 1670 kilometers high; the atmosphere does not have a sharp upper boundary.

The presence of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, in Pluto's atmosphere creates a temperature inversion, with the average temperature of its atmosphere tens of degrees warmer than its surface[125], though observations by New Horizons have revealed Pluto's upper atmosphere to be far colder than expected (70 K, as opposed to about 100 K)[123]. Pluto's atmosphere is divided into roughly 20 regularly spaced haze layers up to 150 km high[102], thought to be the result of pressure waves created by airflow across Pluto's mountains[123].

Satetlity[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Pluton posiada 5 naturalnych satelitów has five known natural satellites: Charon, odkrytego w 1978 przez astronoma Jamesa Christy; Nix and Hydra, odkryte w 2005[126]; Kerberos, odkryty w 2011[127]; i Styx, odkryty w 2012.[128] Orbity satelitów są okrągłe (ekscentryczność <0,006) i współpłaszczyznowe z równikiem Plutona (nachylenie <1 °)[129][130], dlatego przechylają się o około 120 ° w stosunku do orbity Plutona. System plutoński jest bardzo zwarty: the five known satellites orbit within the inner 3% of the region where prograde orbits would be stable[131]. Closest to Pluto is Charon, which is large enough to be in hydrostatic equilibrium and to cause the barycenter of the Pluto–Charon system to be outside Pluto. Beyond Charon there are four much smaller circumbinary moons, Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra.

The orbital periods of all Pluto's moons are linked in a system of orbital resonances and near resonances[130][132]. When precession is accounted for, the orbital periods of Styx, Nix, and Hydra are in an exact 18:22:33 ratio[130]. There is a sequence of approximate ratios, 3:4:5:6, between the periods of Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra with that of Charon; the ratios become closer to being exact the further out the moons are[130][133].

The Pluto–Charon system is one of the few in the Solar System whose barycenter lies outside the primary body; the Patroclus–Menoetius system is a smaller example, and the Sun–Jupiter system is the only larger one[134]. The similarity in size of Charon and Pluto has prompted some astronomers to call it a double dwarf planet[135]. The system is also unusual among planetary systems in that each is tidally locked to the other, which means that Pluto and Charon always have the same hemisphere facing each other. From any position on either body, the other is always at the same position in the sky, or always obscured[136]. This also means that the rotation period of each is equal to the time it takes the entire system to rotate around its barycenter[83].

In 2007, observations by the Gemini Observatory of patches of ammonia hydrates and water crystals on the surface of Charon suggested the presence of active cryo-geysers[137].

Pluto's moons are hypothesized to have been formed by a collision between Pluto and a similar-sized body, early in the history of the Solar System. The collision released material that consolidated into the moons around Pluto[138].

Szablon:Multiple image</ref>--> 2. Pluto and Charon, to scale. Image acquired by New Horizons on July 8, 2015. 3. Family portrait of the five moons of Pluto, to scale[139]. 4. Pluto's moon Charon as viewed by New Horizons on July 13, 2015 }}

Pochodzenie[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Pochodzenie i tożsamość Plutona od dawna intrygowały astronomów. Jedną z wczesnych hipotez było to, że Pluton był uciekającym księżycem Neptuna[140], który został wyrzucony z orbity przez swój największy obecnie księżyc, Tryton. Teoria ta została ostatecznie odrzucona, gdy badania dynamiczne wykazały, że jest niemożliwe, ponieważ Pluton nigdy nie zbliża się do Neptuna nkrążąc po swojej orbicie[141].

Pluto's true place in the Solar System began to reveal itself only in 1992, when astronomers began to find small icy objects beyond Neptune that were similar to Pluto not only in orbit but also in size and composition. This trans-Neptunian population is thought to be the source of many short-period comets. Pluto is now known to be the largest member of the Kuiper belt,[k] a stable belt of objects located between 30 and 50 AU from the Sun. As of 2011, surveys of the Kuiper belt to magnitude 21 were nearly complete and any remaining Pluto-sized objects are expected to be beyond 100 AU from the Sun.[142] Like other Kuiper-belt objects (KBOs), Pluto shares features with comets; for example, the solar wind is gradually blowing Pluto's surface into space[143]. It has been claimed that if Pluto were placed as near to the Sun as Earth, it would develop a tail, as comets do[144]. This claim has been disputed with the argument that Pluto's escape velocity is too high for this to happen[145].

Though Pluto is the largest Kuiper belt object discovered[109], Neptune's moon Triton, which is slightly larger than Pluto, is similar to it both geologically and atmospherically, and is thought to be a captured Kuiper belt object[146]. Eris (see above) is about the same size as Pluto (though more massive) but is not strictly considered a member of the Kuiper belt population. Rather, it is considered a member of a linked population called the scattered disc.

A large number of Kuiper belt objects, like Pluto, are in a 2:3 orbital resonance with Neptune. KBOs with this orbital resonance are called "plutinos", after Pluto[147].

Like other members of the Kuiper belt, Pluto is thought to be a residual planetesimal; a component of the original protoplanetary disc around the Sun that failed to fully coalesce into a full-fledged planet. Most astronomers agree that Pluto owes its current position to a sudden migration undergone by Neptune early in the Solar System's formation. As Neptune migrated outward, it approached the objects in the proto-Kuiper belt, setting one in orbit around itself (Triton), locking others into resonances, and knocking others into chaotic orbits. The objects in the scattered disc, a dynamically unstable region overlapping the Kuiper belt, are thought to have been placed in their current positions by interactions with Neptune's migrating resonances[148]. A computer model created in 2004 by Alessandro Morbidelli of the Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur in Nice suggested that the migration of Neptune into the Kuiper belt may have been triggered by the formation of a 1:2 resonance between Jupiter and Saturn, which created a gravitational push that propelled both Uranus and Neptune into higher orbits and caused them to switch places, ultimately doubling Neptune's distance from the Sun. The resultant expulsion of objects from the proto-Kuiper belt could also explain the Late Heavy Bombardment 600 million years after the Solar System's formation and the origin of the Jupiter trojans[149]. It is possible that Pluto had a near-circular orbit about 33 AU from the Sun before Neptune's migration perturbed it into a resonant capture[150]. The Nice model requires that there were about a thousand Pluto-sized bodies in the original planetesimal disk, which included Triton and Eris.[149]

Obserwacja i eksploracja[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Odległość Plutona od Ziemi utrudnia jego dogłębne badania i eksplorację 14 lipca 2015 r. Sonda kosmiczna NASA New Horizons przeleciała przez system Plutona, dostarczając wiele informacji na jej temat[151]

Obserwacja[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Widoczna jasność Plutona wynosi średnio 15,1, jaśniej do 13,65 na peryhelium[3]. Aby go zobaczyć, wymagany jest teleskop; pożądany jest otwór około 30 cm (12 cali)[152]. Wygląda jak gwiazda bez widocznego dysku nawet w dużych teleskopach, ponieważ jego średnica kątowa wynosi tylko 0,11 ".

Najwcześniejsze mapy Plutona, zostały wykonane pod koniec lat 80., były mapami jasności utworzonymi z bliskiej obserwacji zaćmień przez jego największy księżyc, Charona. Obserwowano zmiany całkowitej średniej jasności układu Pluton – Charon podczas zaćmień. Na przykład zaćmienie jasnego punktu na Plutonie powoduje większą całkowitą zmianę jasności niż zaćmienie ciemnego punktu. Komputerowe analizy wielu takich obserwacji można wykorzystać do stworzenia mapy jasności. Tą metodą można też śledzić zmiany jasności w czasie[153][154].

Better maps were produced from images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), which offered higher resolution, and showed considerably more detail[91], resolving variations several hundred kilometers across, including polar regions and large bright spots[93]. These maps were produced by complex computer processing, which finds the best-fit projected maps for the few pixels of the Hubble images[155]. These remained the most detailed maps of Pluto until the flyby of New Horizons in July 2015, because the two cameras on the HST used for these maps were no longer in service[155].

Eksploracja[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Sonda New Horizons, która przeleciała w lipcu 2015 koło Plutona, jest pierwszą i jak dotąd jedyną próbą bezpośredniego zbadania Plutona. Rozpoczęła się w 2006 r., Pierwsze (odległe) obrazy Plutona wysłała pod koniec września 2006 r. Podczas testu Long Range Reconnaissance Imager[156]. Obrazy wykonane z odległości około 4,2 miliarda kilometrów potwierdziły zdolność sondy kosmicznej do śledzenia odległych celów, krytycznych dla manewrowania w kierunku Plutona i innych obiektów pasa Kuipera. Na początku 2007 roku jednostka wykorzystała wspomaganie grawitacyjne Jowisza.

New Horizons zbliżyła się do Plutona 14 lipca 2015 r. po 3 462 dniach podróży przez Układ Słoneczny. Obserwacje naukowe Plutona rozpoczęły się na pięć miesięcy przed najbliższym podejściem i trwały przez co najmniej miesiąc po spotkaniu. Obserwacje prowadzono za pomocą pakietu do teledetekcji, który zawierał narzędzia do obrazowania i narzędzie do badań radiowych, a także spektroskopowe i inne eksperymenty. Cele naukowe New Horizons polegały na scharakteryzowaniu globalnej geologii i morfologii Plutona i jego księżyca Charona, odwzorowania składu ich powierzchni i przeanalizowania neutralnej atmosfery Plutona i prędkości jego ucieczki. W dniu 25 października 2016 r., o godzinie. 17:48 ET, sonda przesłała ostatnie dane (w sumie z 50 miliardów bitów danych lub 6.25 gigabajtów) z bliskiego spotkania z Plutonem[157][158][159][160].

Videos[edytuj | edytuj kod]

See also[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Notes[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Przypisy[edytuj | edytuj kod]

- ↑ a b c d M. W. Buie, W. M. Grundy, E. F. Young, L. A. Young, S. A. Stern. Orbits and photometry of Pluto's satellites: Charon, S/2005 P1, and S/2005 P2. „Astronomical Journal”. 132 (1), s. 290, 2006. DOI: 10.1086/504422. arXiv:astro-ph/0512491. Bibcode: 2006AJ....132..290B.

- ↑ Calvin J. Hamilton: Dwarf Planet Pluto. Views of the Solar System, 2006-02-12. [dostęp 2007-01-10]. Błąd w przypisach: Nieprawidłowy znacznik

<ref>; nazwę „Hamilton” zdefiniowano więcej niż raz z różną zawartością - ↑ a b c d e f David R. Williams, Pluto Fact Sheet, NASA, 2015.

- ↑ a b Horizon Online Ephemeris System for Pluto Barycenter, JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris System @ Solar System Dynamics Group. (set Observer Location to @0 to place the observer at the center of the Sun-Jupiter system)

- ↑ Courtney Seligman: Rotation Period and Day Length. [dostęp 2009-08-13].

- ↑ E M Standish, J G Williams: Keplerian Elements for Approximate Positions of the Major Planets. [dostęp 2011-01-12].

- ↑ Błąd w przypisach: Błąd w składni elementu

<ref>. Brak tekstu w przypisie o nazwieyoung07 - ↑ a b Seidelmann, P. Kenneth, et al.. Report of the IAU/IAG Working Group on cartographic coordinates and rotational elements: 2006. „Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy”. 98 (3), s. 155–180, 2007. DOI: 10.1007/s10569-007-9072-y. Bibcode: 2007CeMDA..98..155S.

- ↑ AstDys (134340) Pluto Ephemerides. Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. [dostęp 2010-06-27]. Błąd w przypisach: Nieprawidłowy znacznik

<ref>; nazwę „AstDys-Pluto” zdefiniowano więcej niż raz z różną zawartością - ↑ JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 134340 Pluto. [dostęp 2008-06-12]. Błąd w przypisach: Nieprawidłowy znacznik

<ref>; nazwę „jpldata” zdefiniowano więcej niż raz z różną zawartością - ↑ Pluto has carbon monoxide in its atmosphere

- ↑ Błąd w przypisach: Błąd w składni elementu

<ref>. Brak tekstu w przypisie o nazwiegłosowania - ↑ Ken Croswell, Planet Quest: The Epic Discovery of Alien Solar Systems, New York: The Free Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0-684-83252-4.

- ↑ a b c Clyde W. Tombaugh, The Search for the Ninth Planet, Pluto, „Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets”, 5, 1946, s. 73–80, Bibcode: 1946ASPL....5...73T.

- ↑ a b c William G. Hoyt, W. H. Pickering's Planetary Predictions and the Discovery of Pluto, „Isis”, 4, 67, 1976, s. 551–564, DOI: 10.1086/351668.

- ↑ Mark Littman, Planets Beyond: Discovering the Outer Solar System, Wiley, 1990, ISBN 0-471-51053-X.

- ↑ Greg Buchwald, Michael Dimario, Walter Wild, Pluto is Discovered Back in Time, „Amateur—Professional Partnerships in Astronomy”, 220, San Francisco: San Francisco: Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 2000, ISBN 1-58381-052-8, Bibcode: 2000ASPC..220..355B.

- ↑ a b Croswell 1997 ↓, s. 50.

- ↑ Croswell 1997 ↓, s. 52.

- ↑ For example: "Ninth Planet Discovered on Edge of Solar System: First Found in 84 Years". Associated Press. The New York Times. March 14, 1930. p. 1.

- ↑ a b Joe Rao, Finding Pluto: Tough Task, Even 75 Years Later, Space.com, 2005.

- ↑ Brad Mager, The Search Continues [online], Pluto: The Discovery of Planet X.

- ↑ a b c d Paul Rincon, The girl who named a planet [online], BBC News, 2006.

- ↑ Croswell 1997 ↓, s. 54–55.

- ↑ Pluto Research at Lowell [online].

- ↑ NASA's Solar System Exploration: Multimedia: Gallery: Pluto's Symbol, NASA [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ Allison M. Heinrichs, Dwarfed by comparison [online], Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, 2006 [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ David L. Clark, David E. Hobart, Reflections on the Legacy of a Legend [online], 2000.

- ↑ Steve Renshaw, Saori Ihara, A Tribute to Houei Nojiri [online], 2000 [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ a b c Planetary Linguistics [online] [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ Bathrobe', Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto in Chinese, Japanese, and Vietnamese [online], cjvlang.com [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ Alan Stern, David James Tholen, Pluto and Charon, University of Arizona Press, 1997, s. 206–208, ISBN 978-0-8165-1840-1.

- ↑ Andrew Claude de la Cherois Crommelin, The Discovery of Pluto, „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, 4, 91, 1931, s. 380–385, DOI: 10.1093/mnras/91.4.380, Bibcode: 1931MNRAS..91..380..

- ↑ a b Seth B. Nicholson, Nicholas U. Mayall, The Probable Value of the Mass of Pluto, „Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific”, 250, 42, 1930, DOI: 10.1086/124071, Bibcode: 1930PASP...42..350N.

- ↑ Seth B. Nicholson, Nicholas U. Mayall, Positions, Orbit, and Mass of Pluto, „The Astrophysical Journal”, 73, 1931, DOI: 10.1086/143288, Bibcode: 1931ApJ....73....1N.

- ↑ a b Gerard P. Kuiper, The Diameter of Pluto, „Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific”, 366, 62, 1950, s. 133–137, DOI: 10.1086/126255, Bibcode: 1950PASP...62..133K.

- ↑ a b Croswell 1997 ↓, s. 57.

- ↑ James W. Christy, Robert Sutton Harrington, The Satellite of Pluto, „Astronomical Journal”, 8, 83, 1978, s. 1005–1008, DOI: 10.1086/112284, Bibcode: 1978AJ.....83.1005C.

- ↑ a b Marc W. Buie i inni, Orbits and photometry of Pluto's satellites: Charon, S/2005 P1, and S/2005 P2, „Astronomical Journal”, 1, 132, 2006, s. 290–298, DOI: 10.1086/504422, Bibcode: 2006AJ....132..290B, arXiv:astro-ph/0512491.

- ↑ P. Kenneth Seidelmann, Robert Sutton Harrington, Planet X – The current status, „Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy”, 43, 1988, s. 55–68, DOI: 10.1007/BF01234554, Bibcode: 1987CeMec..43...55S.

- ↑ a b E. Myles Standish, Planet X—No dynamical evidence in the optical observations, „Astronomical Journal”, 5, 105, 1993, s. 200–2006, DOI: 10.1086/116575, Bibcode: 1993AJ....105.2000S.

- ↑ Tom Standage, The Neptune File, Penguin, 2000, ISBN 0-8027-1363-7.

- ↑ History I: The Lowell Observatory in 20th century Astronomy, The Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 1994.

- ↑ Neil deGrasse Tyson, Astronomer Responds to Pluto-Not-a-Planet Claim, Space.com, 2001.

- ↑ NASA-Funded Scientists Discover Tenth Planet [online], NASA press releases, 2005.

- ↑ a b Steven Soter, What is a Planet?, „The Astronomical Journal”, 6, 132, 2007, s. 2513–2519, DOI: 10.1086/508861, Bibcode: 2006AJ....132.2513S, arXiv:astro-ph/0608359.

- ↑ IAU 2006 General Assembly: Resolutions 5 and 6, IAU, 2006.

- ↑ a b IAU 2006 General Assembly: Result of the IAU Resolution votes, International Astronomical Union (News Release – IAU0603), 2006.

- ↑ Daniel W.E. Green, (134340) Pluto, (136199) Eris, and (136199) Eris I (Dysnomia), „IAU Circular”, 8747, 2006 [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ JPL Small-Body Database Browser, California Institute of Technology.

- ↑ Robert Roy Britt, Pluto Demoted: No Longer a Planet in Highly Controversial Definition, Space.com, 2006 [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ Sal Ruibal, Astronomers question if Pluto is real planet, USA Today, 1999.

- ↑ Robert Roy Britt, Why Planets Will Never Be Defined, Space.com, 2006.

- ↑ Robert Roy Britt, Scientists decide Pluto's no longer a planet, MSNBC, 2006.

- ↑ a b David Shiga, New planet definition sparks furore, NewScientist.com, 2006.

- ↑ Should Large Moons Be Called 'Satellite Planets'?, News.discovery.com, 2010.

- ↑ Marc W. Buie, My response to 2006 IAU Resolutions 5a and 6a, Southwest Research Institute, 2006 [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ Dennis Overbye, Pluto Is Demoted to 'Dwarf Planet', „The New York Times”, 2006.

- ↑ Edna DeVore, Planetary Politics: Protecting Pluto, Space.com, 2006.

- ↑ Constance Holden, Rehabilitating Pluto, „Science”, 5819, 315, 2007, DOI: 10.1126/science.315.5819.1643c.

- ↑ Joni Marie Gutierrez, A joint memorial. Declaring Pluto a planet and declaring March 13, 2007, 'Pluto planet day' at the legislature, Legislature of New Mexico, 2007.

- ↑ Illinois General Assembly: Bill Status of SR0046, 96th General Assembly, ilga.gov, Illinois General Assembly.

- ↑ Pluto's still the same Pluto, „Independent Newspapers”, 2006.

- ↑ 'Plutoed' chosen as '06 Word of the Year [online], 2007.

- ↑ J.R. Minkel, Is Rekindling the Pluto Planet Debate a Good Idea?, „Scientific American”, 2008.

- ↑ The Great Planet Debate: Science as Process. A Scientific Conference and Educator Workshop, gpd.jhuapl.edu, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, 2008.

- ↑ "Scientists Debate Planet Definition and Agree to Disagree", Planetary Science Institute press release of September 19, 2008, PSI.edu

- ↑ Plutoid chosen as name for Solar System objects like Pluto, Paris: International Astronomical Union (News Release – IAU0804), 2008.

- ↑ "Plutoids Join the Solar Family", Discover Magazine, January 2009, p. 76

- ↑ Science News, July 5, 2008, p. 7

- ↑ Pluto to become most distant planet, JPL/NASA, 1999.

- ↑ Gerald Jay Sussman, Jack Wisdom, Numerical evidence that the motion of Pluto is chaotic, „Science”, 4864, 241, 1988, s. 433–437, DOI: 10.1126/science.241.4864.433, PMID: 17792606, Bibcode: 1988Sci...241..433S.

- ↑ Jack Wisdom, Matthew Holman, Symplectic maps for the n-body problem, „Astronomical Journal”, 102, 1991, s. 1528–1538, DOI: 10.1086/115978, Bibcode: 1991AJ....102.1528W.

- ↑ a b c d James G. Williams, G.S. Benson, Resonances in the Neptune-Pluto System, „Astronomical Journal”, 76, 1971, DOI: 10.1086/111100, Bibcode: 1971AJ.....76..167W.

- ↑ a b c d Xiao-Sheng Wan, Tian-Yi Huang, Kim A. Innanen, The 1:1 Superresonance in Pluto's Motion, „The Astronomical Journal”, 2, 121, 2001, s. 1155–1162, DOI: 10.1086/318733, Bibcode: 2001AJ....121.1155W.

- ↑ Maxwell W. Hunter, Unmanned scientific exploration throughout the Solar System, „Space Science Reviews”, 5, 6, 2004, DOI: 10.1007/BF00168793, Bibcode: 1967SSRv....6..601H.

- ↑ a b c d Renu Malhotra, Pluto's Orbit [online], 1997.

- ↑ a b c Hannes Alfvén, Gustaf Arrhenius, SP-345 Evolution of the Solar System, 1976.

- ↑ C.J. Cohen, E.C. Hubbard, Libration of the close approaches of Pluto to Neptune, „Astronomical Journal”, 70, 1965, DOI: 10.1086/109674, Bibcode: 1965AJ.....70...10C.

- ↑ a b Carlos de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl de la Fuente Marcos, Plutino 15810 ([[:Szablon:Mp]]), an accidental quasi-satellite of Pluto, „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters”, 427, 2012, L85, DOI: 10.1111/j.1745-3933.2012.01350.x, Bibcode: 2012MNRAS.427L..85D, arXiv:1209.3116.

- ↑ Pluto's fake moon [online].

- ↑ New Horizons Collects First Science on a Post-Pluto Object [online].

- ↑ a b Gunter Faure, Teresa M. Mensing, Pluto and Charon: The Odd Couple, Introduction to Planetary Science, Springer, 2007, s. 401–408, DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4020-5544-7, ISBN 978-1-4020-5544-7.

- ↑ Schombert, Jim; University of Oregon Astronomy 121 Lecture notes, Pluto Orientation diagram

- ↑ Joseph L. Kirschvink, Robert L. Ripperdan, David A. Evans, Evidence for a Large-Scale Reorganization of Early Cambrian Continental Masses by Inertial Interchange True Polar Wander, „Science”, 5325, 277, 1997, s. 541–545, DOI: 10.1126/science.277.5325.541, ISSN 0036-8075.

- ↑ James T. Keane i inni, Reorientation and faulting of Pluto due to volatile loading within Sputnik Planitia, „Nature”, 7631, 540, 2016, s. 90–93, DOI: 10.1038/nature20120, PMID: 27851731, Bibcode: 2016Natur.540...90K.

- ↑ Tobias C. Owen i inni, Surface Ices and the Atmospheric Composition of Pluto, „Science”, 5122, 261, 1993, s. 745–748, DOI: 10.1126/science.261.5122.745, PMID: 17757212, Bibcode: 1993Sci...261..745O.

- ↑ Near-infrared spectral monitoring of Pluto's ices: Spatial distribution and secular evolution, „Icarus”, 2, 223, 2013, s. 710–721, DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2013.01.019, Bibcode: 2013Icar..223..710G, arXiv:1301.6284 [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ Nadia Drake, Floating Mountains on Pluto—You Can't Make This Stuff Up, National Geographic, 2015.

- ↑ Marc W. Buie i inni, Pluto and Charon with the Hubble Space Telescope: I. Monitoring global change and improved surface properties from light curves, „Astronomical Journal”, 3, 139, 2010, s. 1117–1127, DOI: 10.1088/0004-6256/139/3/1117, Bibcode: 2010AJ....139.1117B.

- ↑ a b Marc W. Buie, Pluto map information [online] [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ Ray Villard, Marc W. Buie, New Hubble Maps of Pluto Show Surface Changes, News Release Number: STScI-2010-06, 2010.

- ↑ a b Marc W. Buie i inni, Pluto and Charon with the Hubble Space Telescope: II. Resolving changes on Pluto's surface and a map for Charon, „Astronomical Journal”, 3, 139, 2010, s. 1128–1143, DOI: 10.1088/0004-6256/139/3/1128, Bibcode: 2010AJ....139.1128B.

- ↑ a b Błąd w przypisach: Błąd w składni elementu

<ref>. Brak tekstu w przypisie o nazwiePluto System after New Horizons - ↑ Emily Lakdawalla, DPS/EPSC update on New Horizons at the Pluto system and beyond, The Planetary Society, 2016.

- ↑ W.B. McKinnon i inni, Convection in a volatile nitrogen-ice-rich layer drives Pluto’s geological vigour, „Nature”, 7605, 534, 2016, s. 82–85, DOI: 10.1038/nature18289, Bibcode: 2016Natur.534...82..

- ↑ A.J. Trowbridge i inni, Vigorous convection as the explanation for Pluto’s polygonal terrain, „Nature”, 7605, 534, 2016, s. 79–81, DOI: 10.1038/nature18016, PMID: 27251278, Bibcode: 2016Natur.534...79T.

- ↑ Emily Lakdawalla, Pluto updates from AGU and DPS: Pretty pictures from a confusing world, The Planetary Society, 2015.

- ↑ O. Umurhan, Probing the Mysterious Glacial Flow on Pluto’s Frozen ‘Heart’, NASA, 2016.

- ↑ F. Marchis, D.E. Trilling, The Surface Age of Sputnik Planum, Pluto, Must Be Less than 10 Million Years, „PLoS ONE”, 1, 11, 2016, e0147386, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147386, PMID: 26790001, PMCID: PMC4720356, Bibcode: 2016PLoSO..1147386T, arXiv:1601.02833.

- ↑ Szablon:Cite conference

- ↑ a b c d e Błąd w przypisach: Błąd w składni elementu

<ref>. Brak tekstu w przypisie o nazwieStern2015 - ↑ a b c Hauke Hussmann, Frank Sohl, Tilman Spohn, Subsurface oceans and deep interiors of medium-sized outer planet satellites and large trans-neptunian objects, „Icarus”, 1, 185, 2006, s. 258–273, DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005, Bibcode: 2006Icar..185..258H.

- ↑ The Inside Story, pluto.jhuapl.edu – NASA New Horizons mission site, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, 2007.

- ↑ Overlooked Ocean Worlds Fill the Outer Solar System. John Wenz, Scientific American. October 4, 2017.

- ↑ Samantha Cole, An Incredibly Deep Ocean Could Be Hiding Beneath Pluto's Icy Heart, Popular Science.

- ↑ NASA, X-ray Detection Sheds New Light on Pluto [online], nasa.gov, 2016.

- ↑ Robert L. Millis i inni, Pluto's radius and atmosphere – Results from the entire 9 June 1988 occultation data set, „Icarus”, 2, 105, 1993, s. 282–297, DOI: 10.1006/icar.1993.1126, Bibcode: 1993Icar..105..282M.

- ↑ a b c d Michael E. Brown, How big is Pluto, anyway? [online], 2010. (Franck Marchis on 8 November 2010)

- ↑ Eliot F. Young, Richard P. Binzel, A new determination of radii and limb parameters for Pluto and Charon from mutual event lightcurves, „Icarus”, 2, 108, 1994, s. 219–224, DOI: 10.1006/icar.1994.1056, Bibcode: 1994Icar..108..219Y.

- ↑ a b Eliot F. Young, Leslie A. Young, Marc W. Buie, Pluto's Radius, „American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting No. 39, #62.05; Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society”, 39, 2007, Bibcode: 2007DPS....39.6205Y.

- ↑ Angela M. Zalucha i inni, An analysis of Pluto occultation light curves using an atmospheric radiative-conductive model, „Icarus”, 1, 211, 2011, s. 804–818, DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2010.08.018, Bibcode: 2011Icar..211..804Z.

- ↑ a b Emmanuel Lellouch i inni, Exploring the spatial, temporal, and vertical distribution of methane in Pluto's atmosphere, „Icarus”, 246, 2015, s. 268–278, DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2014.03.027, Bibcode: 2015Icar..246..268L, arXiv:1403.3208.

- ↑ a b Szablon:Cite AV media

- ↑ a b c d Błąd w przypisach: Błąd w składni elementu

<ref>. Brak tekstu w przypisie o nazwieNimmo2017 - ↑ John Davies, Beyond Pluto (extract) [online], Royal Observatory, Edinburgh, 2001.

- ↑ Laird M. Close i inni, Adaptive optics imaging of Pluto–Charon and the discovery of a moon around the Asteroid 45 Eugenia: the potential of adaptive optics in planetary astronomy, „Proceedings of the International Society for Optical Engineering”, 4007, European Southern Observatory, 2000 (Adaptive Optical Systems Technology), s. 787–795, DOI: 10.1117/12.390379, Bibcode: 2000SPIE.4007..787C.

- ↑ a b How Big Is Pluto? New Horizons Settles Decades-Long Debate, NASA, 2015.

- ↑ Emily Lakdawalla, Pluto minus one day: Very first New Horizons Pluto encounter science results, The Planetary Society, 2015.

- ↑ Conditions on Pluto: Incredibly Hazy With Flowing Ice [online], New York Times, 2015.

- ↑ Ken Croswell, Nitrogen in Pluto's Atmosphere, New Scientist, 1992.

- ↑ Evidence that Pluto's atmosphere does not collapse from occultations including the 2013 May 04 event, „Icarus”, 246, 2015, s. 220–225, DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2014.03.026, Bibcode: 2015Icar..246..220O.

- ↑ a b c d e Kelly Beatty, Pluto’s Atmosphere Confounds Researchers, Sky & Telescope, 2016.

- ↑ Ker Than, Astronomers: Pluto colder than expected, Space.com (via CNN.com), 2006.

- ↑ Emmanuel Lellouch i inni, Pluto's lower atmosphere structure and methane abundance from high-resolution spectroscopy and stellar occultations, „Astronomy and Astrophysics”, 3, 495, 2009, L17–L21, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200911633, Bibcode: 2009A&A...495L..17L, arXiv:0901.4882.

- ↑ Guy Gugliotta, Possible New Moons for Pluto [online], Washington Post, 2005.

- ↑ NASA's Hubble Discovers Another Moon Around Pluto, NASA, 2011.

- ↑ Mike Wall, Pluto Has a Fifth Moon, Hubble Telescope Reveals [online], Space.com, 2012.

- ↑ M. Buie, D. Tholen, W. Grundy, The Orbit of Charon is Circular, „The Astronomical Journal”, 144, 2012, s. 15, DOI: 10.1088/0004-6256/144/1/15, Bibcode: 2012AJ....144...15B.

- ↑ a b c d M.R. Showalter, D.P. Hamilton, Resonant interactions and chaotic rotation of Pluto’s small moons, „Nature”, 7554, 522, 2015, s. 45–49, DOI: 10.1038/nature14469, PMID: 26040889, Bibcode: 2015Natur.522...45S.

- ↑ S. Alan Stern i inni, Characteristics and Origin of the Quadruple System at Pluto, „Submitted to Nature”, 2005, arXiv:astro–ph/0512599, Bibcode: 2005astro.ph.12599S, arXiv:astro-ph/0512599.

- ↑ Alexandra Witze, Pluto’s moons move in synchrony, „Nature”, 2015, DOI: 10.1038/nature.2015.17681.

- ↑ J. Matson, New Moon for Pluto: Hubble Telescope Spots a 5th Plutonian Satellite [online], Scientific American web site, 2012.

- ↑ Derek C. Richardson, Kevin J. Walsh, Binary Minor Planets, „Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences”, 1, 34, 2005, s. 47–81, DOI: 10.1146/annurev.earth.32.101802.120208, Bibcode: 2006AREPS..34...47R.

- ↑ Bruno Sicardy i inni, Charon's size and an upper limit on its atmosphere from a stellar occultation, „Nature”, 7072, 439, 2006, s. 52–4, DOI: 10.1038/nature04351, PMID: 16397493, Bibcode: 2006Natur.439...52S.

- ↑ Leslie A. Young, The Once and Future Pluto [online], Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado, 1997.

- ↑ Charon: An ice machine in the ultimate deep freeze [online], Gemini Observatory News Release, 2007.

- ↑ NASA's Hubble Finds Pluto’s Moons Tumbling in Absolute Chaos [online].

- ↑ HubbleSite – NewsCenter – Hubble Finds Two Chaotically Tumbling Pluto Moons (06/03/2015) – Introduction [online].

- ↑ Willy Ley, The Demotion of Pluto, 1956, s. 79–91.

- ↑ S. Alan Stern, David J. Tholen, Pluto and Charon, University of Arizona Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0-8165-1840-1.

- ↑ Scott S. Sheppard i inni, A Southern Sky and Galactic Plane Survey for Bright Kuiper Belt Objects, „Astronomical Journal”, 4, 142, 2011, s. 98, DOI: 10.1088/0004-6256/142/4/98, Bibcode: 2011AJ....142...98S, arXiv:1107.5309.

- ↑ Colossal Cousin to a Comet?, pluto.jhuapl.edu – NASA New Horizons mission site, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ Neil deGrasse Tyson, Pluto Is Not a Planet [online], The Planetary Society, 1999 [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ "Nine Reasons Why Pluto Is a Planet" by Philip Metzger

- ↑ Neptune's Moon Triton [online], The Planetary Society [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ David C. Jewitt, The Plutinos [online], University of Hawaii, 2004 [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ Joseph M. Hahn, Neptune's Migration into a Stirred–Up Kuiper Belt: A Detailed Comparison of Simulations to Observations, Saint Mary's University, 2005.

- ↑ a b Harold F. Levison i inni, Origin of the Structure of the Kuiper Belt during a Dynamical Instability in the Orbits of Uranus and Neptune, „Icarus”, 1, 196, 2007, s. 258–273, DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2007.11.035, Bibcode: 2008Icar..196..258L, arXiv:0712.0553.

- ↑ Renu Malhotra, The Origin of Pluto's Orbit: Implications for the Solar System Beyond Neptune, „Astronomical Journal”, 110, 1995, DOI: 10.1086/117532, Bibcode: 1995AJ....110..420M, arXiv:astro-ph/9504036.

- ↑ Tricia Talbert, Top New Horizons Findings Reported in Science [online], NASA, 2016.

- ↑ This month Pluto's apparent magnitude is m=14.1. Could we see it with an 11" reflector of focal length 3400 mm?, Singapore Science Centre, 2002 [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ Eliot F. Young, Richard P. Binzel, Keenan Crane, A Two-Color Map of Pluto's Sub-Charon Hemisphere, „The Astronomical Journal”, 1, 121, 2001, s. 552–561, DOI: 10.1086/318008, Bibcode: 2001AJ....121..552Y.

- ↑ Marc W. Buie, David J. Tholen, Keith Horne, Albedo maps of Pluto and Charon: Initial mutual event results, „Icarus”, 2, 97, 1992, s. 221–227, DOI: 10.1016/0019-1035(92)90129-U, Bibcode: 1992Icar...97..211B.

- ↑ a b Marc W. Buie, How the Pluto maps were made [online] [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ New Horizons, Not Quite to Jupiter, Makes First Pluto Sighting, pluto.jhuapl.edu – NASA New Horizons mission site, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, 2006 [zarchiwizowane z adresu].

- ↑ Kenneth Chang, No More Data From Pluto [online], New York Times, 2016.

- ↑ Pluto Exploration Complete: New Horizons Returns Last Bits of 2015 Flyby Data to Earth, Johns Hopkins Applied Research Laboratory, 2016.

- ↑ Dwayne Brown, Michael Buckley, Maria Stothoff, January 15, 2015 Release 15-011 – NASA's New Horizons Spacecraft Begins First Stages of Pluto Encounter [online], NASA, 2015.

- ↑ New Horizons [online].

Błąd w przypisach: Znacznik <ref> o nazwie „Physorg April 19, 2011”, zdefiniowany w <references>, nie był użyty wcześniej w treści.

Błąd w przypisach: Znacznik <ref> o nazwie „Archinal”, zdefiniowany w <references>, nie był użyty wcześniej w treści.

<ref> o nazwie „TOP2013”, zdefiniowany w <references>, nie był użyty wcześniej w treści.Further reading[edytuj | edytuj kod]

- Stern, S A and Tholen, D J (1997), Pluto and Charon, University of Arizona Press ISBN 978-0816518401

Linki zewntrzne[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Szablon:Sisterlinks Szablon:Refbegin

- New Horizons homepage

- Pluto Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- NASA Pluto factsheet

- Website of the observatory that discovered Pluto

- Earth telescope image of Pluto system

- Keck infrared with AO of Pluto system

- Meghan Gray, Pluto, Sixty Symbols, Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham, 2009.

- Video – Pluto – viewed through the years (GIF) (NASA; animation; July 15, 2015).

- Video – Pluto – "FlyThrough" (00:22; MP4) (YouTube) (NASA; animation; August 31, 2015).

- "A Day on Pluto Video made from July 2015 New Horizon Images" Scientific American

- NASA CGI video of Pluto flyover (July 14, 2017)

- CGI video simulation of rotating Pluto by Seán Doran (see album for more)

- Google Pluto 3D, interactive map of the dwarf planet

Szablon:Refend Szablon:Navboxes

Zobacz też[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Bibliografia[edytuj | edytuj kod]

- K. Croswell: Planet Quest: The Epic Discovery of Alien Solar Systems. The Free Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-684-83252-4.

Linki zewnętrzne[edytuj | edytuj kod]

- Pluto Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- NASA Pluto factsheet

- Website of the observatory that discovered Pluto

Szablon:Pluton Szablon:Trans-Neptunian dwarf planets Szablon:Trans-Neptunian objects Szablon:MinorPlanets Navigator

Uwagi[edytuj | edytuj kod]

- ↑ The HST observations were made in two wavelengths, which is insufficient to directly make a true colour image. However, the surface maps at each wavelength do limit the shape of the spectrum that could be produced by the materials that are potentially on Pluto's surface. These spectra, generated for each resolved point on the surface, are then converted to the RGB colour values seen here. See Buie et al, 2010.

- ↑ Surface area derived from the radius r: .

- ↑ Volume v derived from the radius r: .

- ↑ Surface gravity derived from the mass m, the gravitational constant G and the radius r: .

- ↑ Escape velocity derived from the mass m, the gravitational constant G and the radius r: Szablon:Math.

- ↑ Based on the orientation of Charon's orbit, which is assumed the same as Pluto's spin axis due to the mutual tidal locking.

- ↑ Based on geometry of minimum and maximum distance from Earth and Pluto radius in the factsheet

- ↑ In US dictionary transcription, Szablon:USdict. From the (łac.) Plūto

- ↑ Wartość obliczana na podstawie danych inflacji Wielkiej Brytanii:

- 1700 do lat obecnych: MeasuringWorth, UK Retail Price Index (Annual Observations in Table and Graphical Format 1700 to the Present) - UK GDP Deflator (ang.)

- najnowszy rok (prognoza): World Economic Outlook Databases (Data - World Economic Outlook Databases (WEO), more) [online], Najnowszy wpis - By Countries - Major advanced economies (G7) - United Kingdom - Gross domestic product, deflator - Start Year: akt. rok - 2, End Year: akt. rok, IMF [dostęp 2021-07-17] (ang.).

- ↑ a b Błąd w przypisach: Błąd w składni elementu

<ref>. Brak tekstu w przypisie o nazwie{{{1}}}

Kategoria:Nazwane planetoidy Kategoria:Obiekty astronomiczne odkryte w 1930